Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797)

Sandrine Bergès considers the too short wanderings of a political philosopher.

Mary Wollstonecraft is more popular now than at possibly any other time after her death. A campaign has been waged to install a statue of her in Newington Green, London, where she lived and worked for some years; her portrait was even projected onto the British Houses of Parliament. Yet there is something a bit shallow and unsatisfying about how she is popularly being remembered: as the ‘mother of feminism’ – a title that gets bandied about whenever an early female author is rediscovered; as a scandalous single mother – the reason why readers avoided her books through the nineteenth century; or as the mother of the author of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley. There’s a lot more to Mary Wollstonecraft than motherhood. Over the last ten years her work as a philosopher has come under increasing scrutiny, and as a result it is now valued, if not as it should be, at least in a way that promises it may become so. She is increasingly recognized as an important actor in the revival of neo-Roman republicanism, emphasizing civic virtues and participation, as well as liberty and non-domination. Her contribution to that tradition is important in particular because her republicanism is more inclusive than it was for many of her contemporaries. Reading her allows us to grasp how it is possible to be, for instance, a feminist and a republican – a combination which has given rise to a number of doubts on the part of women philosophers. The depth and richness of Mary Wollstonecraft’s philosophy is especially impressive given that she died at the age of thirty-eight. But even her private life deserves more scrutiny than it sometimes receives.

Once we look at what she achieved in her lifetime, it’s actually quite easy to avoid portraying her exclusively in terms of motherhood. Most of her thirty-eight years were spent travelling, and she never put down roots. This is why we don’t have much physical evidence of her life: there isn’t a family mansion, or even a townhouse, where we can peruse her books, see the desk she wrote at every morning, or the room she slept in every night. As a child she moved around through necessity, and as an adult, through choice. Her itinerant childhood is a large part of what shaped her, and her adulthood travels are essential to her philosophy, so let’s look at these in turn.

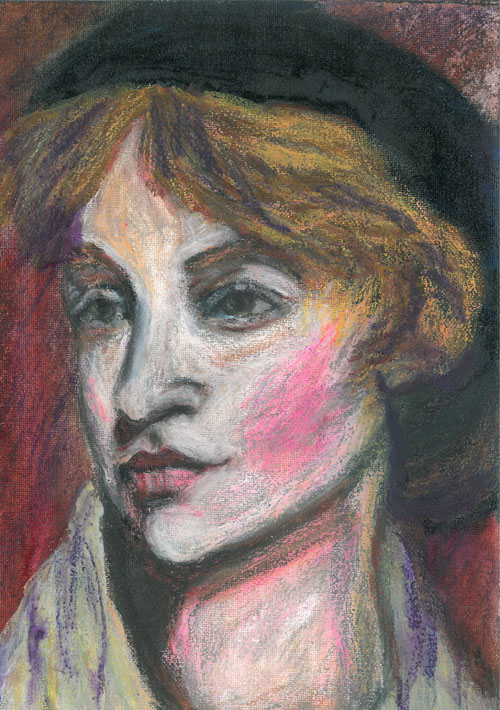

Mary Wollstonecraft by Gail Campbell 2018

An Itinerant Childhood

Mary Wollstonecraft was born in 1759 in London. Due to her father’s gambling and drinking, her middle-class family had to move frequently, and Wollstonecraft’s education was neglected. As a result, she was mostly self-taught – something she was both proud of and at times bothered by. On one occasion the family was able to settle down long enough for Wollstonecraft to attend school for a while. This was in Beverley, near Hull, where she made a friend, Jane Arden, whose father had a large library – the first of several private libraries which played a big role in her education.

Wollstonecraft’s father was a violent man, and while in her autobiographical novel Mary she complains of her mother’s lack of interest in her, she tells us that she used to sleep in front of her mother’s bedroom door to protect her on nights when her father drank. No doubt this experience of living with a violent father gave her an early understanding of what the dependency of women in marriage could mean.

As soon as she was old enough, she took a job as a lady’s companion to a Mrs Dawson in Bath. She remained there for eighteen months, suffering boredom and depression, then spent three months in Windsor. Then her mother became ill, so she moved back home to nurse her until her death. That time was not entirely miserable, however, as she befriended a neighbouring couple, Mr and Mrs Clare. Like Mr Arden before them, they let Wollstonecraft use their library. They also introduced her to a woman who became a very close friend, Fanny Blood.

Newington Green, Portugal & Ireland

After her mother’s death, Wollstonecraft moved in with Fanny’s family, helping Mrs Blood with her embroidery work. Later, with Wollstonecraft’s sisters, the young women decided to start a school for girls, renting a building with the help of members of the Dissenting community in Newington Green, then a village. It is from this experience that Wollstonecraft derived much of her philosophy of education, rightly correcting Rousseau’s claims that little girls cannot be taught as little boys can, especially when it comes to the more abstract disciplines, by pointing out that (unlike him) she had actually taught little girls.

Fanny became ill with consumption, and the doctor recommended that she move to warmer climes, so she joined her fiancé in Portugal. They married, and within a few months, she was pregnant. Unfortunately the pregnancy did not relieve her tuberculosis. She became critically ill, so Wollstonecraft travelled to Portugal to help. She enjoyed the journey, and was one of the few passengers not to get ill during the crossing, helping to nurse others. She could not help Fanny, though, who died shortly after giving birth. Wollstonecraft stayed in Lisbon for a month, caring for Fanny’s child. She used her time there to observe Portuguese customs, and came away convinced that Catholicism was not a healthy religion, and that the Portuguese were particularly bad in their treatment of women and of the lower classes.

When Wollstonecraft returned from Portugal she found that her sisters had not made a success of the school. Her first recourse to get out of debt was to write a book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1786), in which she began to develop arguments for greater gender equality in education, in particular where the development of abstract thinking is concerned. Tellingly, she also advocated that young women travel abroad before they married, arguing that this was how men got an unfair advantage over their wives, having been allowed to experience the world and learn to make their way in it before settling down to build a home and family.

The book sold well, but Wollstonecraft was still in debt. In order to pay it off she learnt French and took up a position as governess to an aristocratic family in Ireland. But she did not flourish there, as she resented her employers’ superficiality and tyrannical tendencies. She did however make a lifelong friend and admirer of one of her charges, Margaret, and she again used her time to build up her store of ideas. Her frequent comments on the negative impact of aristocratic manners on society in general and little girls in particular no doubt come from what she observed in Ireland.

She did though benefit from the use of her employers’ library, where she read Rousseau. Inspired by his mixture of autobiography, fiction, and philosophy, she planned a book, named after herself. Mary told the story of a young woman neglected as a child but who develops her own intellect through reading and writing. Mary is disappointed, first in friendship, then in love, but she finally settles into a non-carnal love relationship.

The London Years

Wollstonecraft eventually lost her governess job – her dislike of her employers and her honesty must have made it unlikely for her to remain long in their employ. She came back to London. The first person she visited was her publisher, Joseph Johnson. He immediately offered her rooms above his shop and a job as translator and reviewer for his Analytical Review. She stayed in London between 1787 and 1792. But she continued to work for Johnson until her death in 1797.

Having a job with a publisher meant that Wollstonecraft did not need to shop for subscribers before she could write a book. Johnson knew what would sell, and was open to suggestions. He was particularly keen on educational works, so gladly took on Wollstonecraft’s next two books; a primer for young ladies, and Original Stories for Children. These early works presaged the strong commitment to education she maintained throughout her career.

It was not until 1790 that Wollstonecraft emerged as a republican philosopher. When Edmund Burke in his pamphlet against the French Revolution attacked her friend and mentor, Richard Price, Wollstonecraft wrote the first reply – her Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790). Here she first articulated her belief that to be free means to be free from domination, and that it is important to be independent to the extent that one is capable of and able to make one’s own decisions. In the Rights of Men, Wollstonecraft defended the republican ideals of the revolution, arguing that the poor of France were in an intolerable relation of dependence towards the rich they could not easily break out of, because part of that relation involved the stunting of their capacity for independent thought. So a French serf before the revolution was dependent because they could not afford to stand up to their master and because they had not the intellectual resources to know what it would mean to do so. Wollstonecraft’s first philosophical fight was thus on behalf of the poor, not specifically women. However, a woman whose material life depends on her husband is equally unfree, even if she does not realise it, because there are a number of choices she simply could not make for herself without her husband’s approval, such as to travel. In this sense, an unequal marriage is as much a tyrannical state as the relation of master and slave.

Johnson printed her book (although he didn’t print Thomas Paine’s later reply to Burke, The Rights of Man, 1791). When he saw that Wollstonecraft was falling into a bout of depression, Johnson also suggested that she write a defense of women’s rights. She did. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), she turns to the question of how republicanism might affect women, and in particular, how their lack of education prepares them for a life of being dominated. Presaging the idea that the oppressed sometimes adapt their mentality to fit their reality, Mary Wollstonecraft argued that dominated individuals often lose the will to reclaim their freedom. Instead, they come to ‘hug their chains’ and think of their condition as normal, sometimes even desirable.

Once the second edition of her Vindication of the Rights of Woman was out, it was Johnson again who suggested that Wollstonecraft go to Paris, to write about the revolution.

The Revolutionary Years

Wollstonecraft arrived in Paris at the end of 1792, just as the trial of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette was beginning. She wrote that Louis being driven to the courthouse was one of the first sights she witnessed there, and that it made her cry.

Possibly she was feeling tearful anyway: her French, learned hastily for the sole purpose of teaching, was not quite up to conversing with the Parisians, and she knew very few people there. This changed quickly as John Christie, Johnson’s colleague, introduced her to the community of foreigners who convened at the salon of the poet Helen Maria Williams. Wollstonecraft’s second Vindication had already been translated into French and had been favourably reviewed, so she was known and welcomed. There she met Thomas Paine, and through him the supporters of the Girondin faction, Monsieur and Madame Roland, and perhaps Condorcet and Brissot. She also met Gilbert Imlay, an American entrepreneur who became her lover. By 1794 she was \pregnant by him. She registered (falsely) as his wife at the American embassy so as to avoid being imprisoned as an English woman, then moved for safety, first to the suburbs, and after she had given birth to her daughter Fanny, to Le Havre.

During her two and half years in France, she wrote. She had started with the intention of penning a series of letters for Johnson on her observations, but she decided instead to write a multi-volume history of the revolution. The first volume came out while she was in Le Havre. The others were never written.

Despite her initial disappointment when she witnessed the beginnings of the Terror, Wollstonecraft’s stance on the Revolution remained positive. Mistakes had been made, which was inevitable; but France was nevertheless working towards the eradication of tyranny. Her book An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution (1795) was a critical study of a number of key documents written in the early years of the revolution by Mirabeau, Brissot, etc., and is concerned with the pursuit of liberty.

Scandinavia

Once her first baby was born and her book written, Wollstonecraft decided it was time to go home and settle down with Imlay. He had just returned to London himself, so she decided to join him there; but she found him living with an opera singer. Wollstonecraft attempted suicide for the first time then. Imlay, rather than simply giving her what she wanted, attempted to rescue her from her depression by giving her something to do. He had lost a shipment of silver he had smuggled out of France, and suspected that the ship’s captain was hiding it somewhere in Scandinavia. He gave Wollstonecraft a right of attorney, and she set out north on a detective mission with her infant daughter and French maid. While she was there, Wollstonecraft wrote Letters written in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796), which were social and political as well as aesthetical reflections on Scandinavia.

Mary’s daughter, Mary, by Bofy

Image © Bofy 2018. Please visit worldofbofy.com

Final Abodes

When she came back from Scandinavia the situation with Imlay hadn’t improved and she tried to kill herself again. This time her friend Mary Hays nursed her back into life. She also reintroduced her to the philosopher William Godwin, whom she had met once at Johnson’s. The two became lovers, and they married in 1797, after she found out she was again pregnant. Even then Wollstonecraft did not put down roots, and chose to retain her independence by living apart from her husband (in an adjacent building).

During her pregnancy she worked on a novel – Maria, or the Wrongs of Woman. It is a sort of literary case study in how domination can harm women no matter their social background. It tells the story of the eponymous aristocrat, married to a tyrannical man who has her imprisoned in an asylum so that she cannot leave him and take their child with her. Jemima, her jailor, is a poor woman who had been abused from childhood and lived on the streets and as a prostitute until by luck she was able to educate herself and gain this job. The novel tells how the two women slowly learn to trust each other, looking at what they have in common as well as their differences.

During that time Wollstonecraft also started a book on child-rearing, which emphasized the equal roles of mother and father, and made notes for another philosophical treatise – possibly the second volume of the Vindication. However, she did not complete any of these, as she died of puerperal fever in September 1797, ten days after giving birth to her second daughter, Mary.

Even after death, there was no settling down. William buried his wife in Old Saint Pancras cemetery. Later, when the dead of St Pancras had to be displaced to make room for the new train station, Mary Shelley’s grandson had the bodies of his great-grand-parents Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin moved to his family plot in Bournemouth.

Fanny Imlay, Mary Wollstonecraft’s first daughter, committed suicide in her thirties. Her second daughter Mary Shelley (neé Godwin) inherited her mother’s love of adventure, and travelled throughout Europe with her husband Percy and their friends, going on to write Frankenstein. Margaret Kings, Mary Wollstonecraft’s favourite pupil when she was a governess in Ireland, also took up travelling, embarking on a grand tour of Europe; and later, dressing as a man, studied medicine in Italy. She eventually settled down in Italy, with Mary Shelley and friends as frequent guests.

© Sandrine Bergès 2018

Sandrine Bergès is associate professor in philosophy at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey. She is the author of The Routledge Companion to Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (2013) and co-editor of The Social and Political Philosophy of Mary Wollstonecraft (2016) with Alan Coffee. She is a co-founder of the Mary Wollstonecraft Philosophical Society: marywollstonecraftphilosophicalsociety.org. sandrineberges.com sandrineberges@gmail.com