Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Street Philosopher

Destined In Delhi

Seán Moran contemplates kismet and choreography.

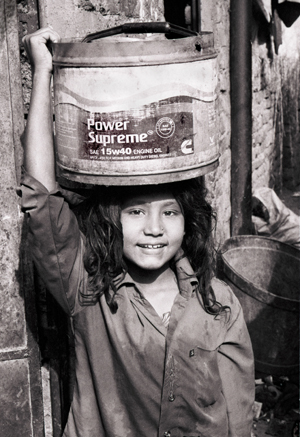

Photo © Seán Moran 2020

This girl lives in an artists’ colony in Delhi. Although her makeshift water bucket says ‘Power Supreme’, India is a country where many people are disempowered, by both gender and caste. This is not America, where anyone can be President. The odds are stacked against a poor girl becoming the Prime Minister of India, or attaining any position of power, supreme or otherwise. She’s carrying water because her home has no plumbing. Her mother cooks out in the open air, over a fire on the ground. I hope that the girl has a flourishing life, whatever direction it takes.

The artists in the colony are professional snake charmers, magicians, drummers and dancers. Despite their grim living conditions, the residents were welcoming. I was offered home-cooked food by people who probably didn’t have enough to eat, but I didn’t insult them by refusing.

I was there to teach local children some Irish jigs and hornpipes on the tin whistle. (The next time you’re in Delhi listen out for any Indian street musicians playing jaunty Irish tunes – and maybe give a decent tip to one of my former students.) In return, they taught me a Hindi song made famous by Bollywood megastar Shah Rukh Khan. I performed it on a bridge in Paris recently and some Indian tourists filmed me on their phones. There are some self-righteous folks who would complain about my ‘appropriation’ of Indian culture, but such sniping is never from Indians. In fact, Shah Rukh Khan himself retweeted the video of me singing his song, playing the flute, and dancing. It went viral for a while, earning the approval of an astounding number of Indians. My musical performance was rightly seen as homage, not appropriation. But I enjoyed the absurdity of achieving brief international fame as a clodhopping dancer.

Unlike me, the girl in my photograph has such grace, balance, and poise that she could make a living as a dancer, as do many of her friends and neighbours in the colony. There are genetic and environmental pressures nudging her towards such a life. As Josephine Donovan wrote, shaping her future is an “intrinsic teleological choreographic program – whatever one may call it (entelechy, psyche, soul, or DNA code)” (Between the Species, 2018). But neither her DNA nor her upbringing fully ‘choreographs’ or determines her life, since she is also a ‘caring purposive subject’, not just an object of genetic and social compliance.

All she can do – all any of us can do – is play the hand that fate has dealt us. However, the card game metaphor is inexact, because our ability or inability to play the hand is part of the hand itself. Some people not only chance upon a poor start in the lottery of life; they’re also hampered by an inherited inability to do anything about it. Others win a grand start plus the genetic endowment to make the most of their early privilege. Let’s not be too pessimistic, though: neither genetic nor social determinism is the whole story. We can sometimes rise above our initial circumstances. Moreover, being a duke or a president is no guarantee of happiness, either for themselves or for those whose paths they cross. Nevertheless, blaming the underprivileged for their plight, or praising the successful for their achievements, is like chastising dice-players for throwing a one, or congratulating them for a six. Sheer determination or a kind mentor can help to overcome disadvantage; but chance is still a major factor – including being genetically predisposed towards resilience in adversity, or being lucky enough to find the right mentor.

Every one of us is dependent on random events which shape our trajectories. Given slightly different circumstances, we could all have turned out to be a rich (wo)man, poor (wo)man, beggar (wo)man, or thief. The last possibility is unsettling. But if we were brought up in a family of pickpockets, would we necessarily have the independence of mind to reject our domestic ethos and follow another path, like Billy Elliot dancing his way out of a mining family?

La Danse Voleur

Talking of which, have you ever seen a pickpocket dance? I have; and it was strangely moving. I was playing my flute and singing the popular French song Aux Champs Élysées in Paris one day (what better way to fund street philosophy research than street performance?). Just as I started belting out the chorus a gang of teenage pickpockets walked past, looking for tourists to rob. They took a furtive peek at the contents of my hat and… started to dance.

I have no affection for pickpockets – my phone was stolen at Pigalle Metro station – but this little vignette made me realise that they were just innocent children at heart. Well, not innocent, perhaps; but children nonetheless – taking a break from their child labour to perform a playful, spontaneous dance.

Some of those youngsters may graduate to more serious crime, while others could conceivably earn a more honest living, perhaps as lawyers. The ‘intrinsic teleological choreographic program’ of humans is not a fixed algorithm, but can be over-ridden by the individual. Not so in the case of other animals, whose ‘choreographies’ are pretty much fixed; their behaviour genetically shaped by their survival value. For example, nocturnal dung beetles of the species Scarabaeus satyrus have a remarkable gift. To survive, they must roll a ball of dung away from the dung-heap quickly, or rival beetles will steal it. So, according to Foster et al (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2017), they give a ‘stellar performance’ of navigating in a straight line. That’s no empty phrase: the beetles actually use the stars to guide their route. But, even more fascinatingly, before they set off, they climb on top of their dung-ball and perform an ‘orientation dance’ to align themselves with celestial features in the night sky. I just love the symbolism of the whole fol-de-rol: gazing up at the stars and dancing, in-between scrabbling about in the dirt.

Although the diet of nocturnal scarab beetles may be distasteful to us, these creatures were sacred to the Ancient Egyptians. After all, the god Khepri’s night-time mission was to roll the setting sun through the underworld, to be ready for sunrise on the opposite horizon the next day.

Socrates As Satyr

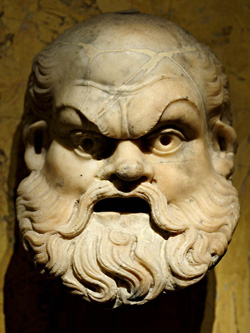

Socrates. Or Silenus.

If an insect satyr, Scarabaeus satyrus, was seen as divinely gifted, so too was a human satyr: Socrates. The politician Alcibiades describes Socrates as being similar to: “the Silenus-figures that sit in the statuaries’ shops; those, I mean, which our craftsmen make with pipes or flutes in their hands: when their two halves are pulled open, they are found to contain images of gods” (Plato, Symposium). In myth, Silenus was an ancestor of the satyrs: ugly, bawdy, drunken wild men of the woods.

Alcibiades, who was not ugly, but did have a thing for Socrates, and was far from sober at the time, tells the assembled drinkers not to be fooled by Socrates’ appearance, for it conceals a divine interior:

“Again, he is utterly stupid and ignorant, as he affects. Is not this like a Silenus? It is an outward casing he wears… Whether anyone else has caught him in a serious moment and opened him, and seen the images inside, I know not; but I saw them one day, and thought them so divine and golden, so perfectly fair and wondrous.”

In other words, we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. Some of the least likely people are touched by divinity. If we could see beneath their carapace, maybe everyone, no matter how mired in the gutter they seem to be, would reveal a divine spark. And those whose circumstances are grim need not be grim. Oscar Wilde captures the human predicament pithily in his play Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892). The caddish Lord Darlington, with his hereditary advantages, says, “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” We can all raise our eyes to the stars – to the transcendent – or even dance in the face of adversity. Socrates danced in his old age, and went to the higher world with equanimity when he was unjustly executed.

The Way We Roll

This line of thinking is rejected by the French-Algerian philosopher Albert Camus in his book The Myth of Sisyphus (1942). Camus feels that rather than take a leap of faith and rely on God to provide meaning in an otherwise meaningless life, as another existentialist, Søren Kierkegaard advocates, we should embrace the absurdity of the world heroically, as Sisyphus did in legend. In the ancient story, Sisyphus is condemned by the gods for all eternity to push a boulder up a mountain, watch it roll down, and repeat, ad infinitum. However, by recognising his task as futile, Sisyphus defiantly ‘owns’ it, without the consolation of belief in a more transcendent narrative. Camus admires Sisyphus’s acceptance of his meaningless plight, and his determination to carry on regardless. Personally, I would love to see Sisyphus take occasional breaks from his labours and lift his eyes up from the boulder: he might even dance – to the music of the Rolling Stones, perhaps – with some Bollywood choreography and Irish hornpipe steps just to add a bit of variety.

Life is not usually as bleak as Sisyphus’s drudgery, but we’re all condemned to push our dungy little spheres along, whatever that allegory actually involves for you. As a revolt against the absurdity of our situations, we can pause to gaze idly at the heavens, and do a little dance, metaphorically or literally. Our ‘power supreme’ as humans is to reject both the intrinsic and the extrinsic choreographies imposed on us, and go freestyle for a while. Then we can return to our water-carrying, dung-rolling, pickpocketing, or lawyering, refreshed and empowered.

© Dr Seán Moran 2020

Seán Moran teaches postgraduate students in Ireland, and is professor of philosophy at a university in the Punjab. He is available for weddings and other celebrations.