Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

I Am Dynamite! by Sue Prideaux

Scott Parker looks at Sue Prideaux’s (armour) penetrating biography of Friedrich Nietzsche.

The temptation for any biographer of Friedrich Nietzsche must be to begin in Turin, with the madman sobbing, his arms draped around a horse’s neck. He sinks to the flagstones of the Piazza Carlo Alberto. We learn that he is never to recover. The scene fades out, and we are whisked back to his childhood, to proceed with the tale of how the ‘philosopher of the future’ reached this breaking point. Prideaux instead opts to build her first chapter around Nietzsche’s first meeting with Richard and Cosima Wagner in 1868, when Nietzsche was an undergrad at Leipzig University. This meeting initiated two of the formative relationships in Nietzsche’s personal as well as intellectual life, and allows Prideaux to introduce the reader to her subject at an important turning point for him. Yet in order to contextualize the meeting sufficiently, Prideaux must strain to cram biographical information and historical weight into the early pages, resulting in a muddied narrative. This attempt to seize the reader’s attention with drama serves neither readers new to Nietzsche, for whom it is insufficient, nor readers who are familiar with the philosopher, for whom the hook is superfluous. Starting with the Wagners is no more unnecessary than starting with the horse; but it’s no less unnecessary either.

Now that I’ve delivered my harshest criticism, let me strongly encourage you to stick with Sue Prideaux beyond the first chapter. If you do you’ll be rewarded with a lively and informative account of Nietzsche’s life. Prideaux conveys a sensitive feel for her subject that will inform any reading of Nietzsche’s resounding prose.

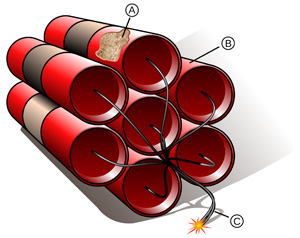

Prideaux takes her title from Nietzsche’s announcement in his autobiography Ecce Homo (1888), “I am not a man, I am dynamite.” She gives us the man who would make such a claim – the very thing that draws readers of Nietzsche to a biography about him. And who was that man?

Often, a sick one. Headaches, nausea, and trouble with vision incapacitated him for days, sometimes weeks, on end. Illness forced him to leave his position as Professor of Philology at the University of Basel, and wander in search of climes that might alleviate his symptoms. “On several occasions,” Prideaux tells us, “he thought his last hour had come” (p.125). Her account of his ongoing sickness serves to illustrate Nietzsche’s aphorism, ‘That which does not kill us makes us stronger’ by allowing us to understand his life through his suffering and what he accomplished despite his suffering. Or was it because of what he suffered? There’s scarcely a better example of making a virtue of necessity than Nietzsche’s distinctive writing style. His headaches, nausea, and bad vision limited his capacity for reading and writing, so he developed the skill of compression. According to Prideaux, brevity became “an increasingly valuable power as the creative intervals between his bouts of illness became shorter, leaving him with the problem of how to communicate his thoughts speedily and to maximum effect before the next attack” (p.34). This casts a very different light on Nietzsche’s explosive aphorisms. Lou Andreas-Salomé, a love interest, and one of the most complex characters in Nietzsche’s life, read even more into the effect of Nietzsche’s illness on his writing. As Prideaux notes, she thought it “enabled him to live numberless lifetimes within the one. She noticed how his life fell into a general pattern. A regular recurrent decline into sickness always demarcated one period of his life from another. Every illness was a death, a dip down into Hades. Every recuperation was a joyful rebirth, a regeneration… During each fleeting recuperation the world gleamed anew. And so each recuperation became not only his own rebirth, but also the birth of a whole new world, a new set of problems that demanded new answers” (p.202). Such rebirths in Nietzsche’s thinking are sketched rather than detailed by Prideaux – which is not a knock on the book but a reminder that it is not a primer on Nietzsche’s philosophy but a biography.

In Beyond Good and Evil (1886) Nietzsche wrote that all philosophy is unconscious autobiography. What then is the biography of a philosopher? To what should such a biography aspire? In Nietzsche’s case at least, the biography is a genealogy of his writing, rounding out and contextualizing the autobiography. If we come to Prideaux knowing who Nietzsche is through his writing, whether we are thrilled or offended by him, we still might come asking from what context such a writer emerged. His illness was, of course, only one of the contingencies around which his life and his writing grew. For another, Prideaux offers Nietzsche at eleven, when he had his own bedroom for the first time. It was then that “he quickly fell into the habit of working till around midnight and getting up at five in the morning to resume” (p.23).

Knowing some of the key contingencies surrounding a writer’s work can help us to appreciate the work itself; and, as in the case of Nietzsche’s misogyny, perhaps understand it. He was not above letting his humiliation at being rejected by Lou, with whom he shared “the most exquisite experience of his life” (p.204) – an ascent of Monte Sacro – and his frustration with his mother and sister, affect his attitude toward women generally. In less reactionary periods, though, as Prideaux writes, “his sympathy for women and his insight into their psychology is remarkable for its time” (p.201). Prideaux points her readers towards 1882’s The Gay Science for examples of the more forward-thinking Nietzsche. In Aphorism 71 of Book Two he criticises the “amazing and monstrous… upbringing of upper-class women” that involves linking sex with shame before sending them ignorantly into a marriage.

Dynamite diagram © Pbroks13 2018

Unlike the charge of misogyny, acquitting Nietzsche of anti-Semitism is easily accomplished, and Prideaux continues her timeline beyond Nietzsche’s death to do so. That this must be done again and again is largely due to Nietzsche’s state after his nervous collapse in Turin, where he became largely unable to communicate coherently. He understood throughout his life that madness was a possibility. But more than that, he also understood madness as “the only engine strong enough to drive change through the morality of custom” (p.335). Nietzsche’s men of the future, the Übermenschen, were those who could escape the grip of conventional moral codes and find their own individual meaning. Anyone who aspired to such greatness must be willing to pay a price – either accepting madness or at least pretending to be mad. Nietzsche was always ready, perhaps eager, to do so, even if it could leave him at the mercy of his cunning, anti-Semitic, Nazi-sympathising sister Elisabeth.

Over the past half century Nietzsche’s legacy has increasingly shaken off the image his sister created of him, and his influence has grown accordingly. Prideaux is near her best when she demonstrates Nietzsche’s ongoing appeal by simply voicing some of his deepest concerns in her own words: “What happens when man cancels the moral code on which he has built the edifice of his civilisation? What does it mean to be human unchained from a central metaphysical purpose? Does a vacuum of meaning occur? If so, what is to fill that vacuum? If the life to come is abolished, ultimate meaning rests in the here and now. Given the power to live without religion, man must take responsibility for his own actions” (p.375). As long as Nietzsche’s ideas resonate, the fascination with him will remain. And as long as it does, I Am Dynamite! will find a much-deserved readership.

© Scott F. Parker 2020

Scott F. Parker’s most recent book, A Way Home (Kelson), explores time, home and selfhood in a series of personal essays.

• I Am Dynamite! A Life of Nietzsche, Sue Prideaux, 2018, $30 hb, Tim Duggan Books, 464 pages, ISBN: 978-1524760823